Key Takeaways

- Ampicillin works by breaking down bacterial cell walls, but it also touches the immune system in subtle ways.

- It can suppress certain white‑blood‑cell activities while boosting others, leading to a mixed net effect.

- Changes in gut microbiota caused by ampicillin influence cytokine production and inflammation.

- Short‑term use is usually safe; prolonged courses raise the risk of dysbiosis and opportunistic infections.

- Understanding these interactions helps doctors choose the right antibiotic and patients manage side‑effects.

Ampicillin is a broad‑spectrum, beta‑lactam antibiotic introduced in the 1960s that targets Gram‑positive and some Gram‑negative bacteria. It belongs to the penicillin family and is commonly prescribed for respiratory, urinary‑tract, and gastrointestinal infections.

The immune system - the body's defense network composed of cells, proteins, and tissues - continually scans for invaders. While antibiotics like ampicillin are designed to kill bacteria directly, they also interact with this network, sometimes in unexpected ways.

How Ampicillin Works: A Quick Primer

Ampicillin attacks the bacterial cell wall by binding to penicillin‑binding proteins (PBPs). These proteins are crucial for assembling peptidoglycan, the mesh that gives bacterial walls their strength. When ampicillin blocks PBPs, the wall weakens and the bacteria burst under osmotic pressure - a process called lysis.

Because human cells lack peptidoglycan, ampicillin is generally selective for bacteria. However, the drug’s presence in the bloodstream and tissues can still influence immune cells that encounter the dying bacteria.

Direct Effects on White Blood Cells

Research from 2022 shows that ampicillin modestly alters the activity of neutrophils - the first responders that engulf bacteria. In vitro studies report a 10‑15% decrease in neutrophil oxidative burst after exposure to therapeutic concentrations of ampicillin. The effect is reversible once the drug clears.

Macrophages, another key player, appear less affected. Some animal models even suggest that ampicillin can enhance macrophage phagocytosis of opsonized bacteria, likely because the antibiotic makes bacterial surfaces more “sticky.”

Overall, the net impact on leukocytes is modest: a slight dampening of neutrophil killing balanced by a possible boost in macrophage cleanup.

Cytokine Modulation: The Signalling Shift

Cytokines are the messengers that coordinate inflammation. A handful of clinical trials measured serum levels of interleukin‑6 (IL‑6), tumor necrosis factor‑alpha (TNF‑α), and interferon‑gamma (IFN‑γ) before and after a 7‑day ampicillin regimen.

- IL‑6 fell by an average of 18% in patients with uncomplicated urinary‑tract infections.

- TNF‑α showed a non‑significant dip of about 5%.

- IFN‑γ remained stable, indicating that adaptive immunity was not heavily suppressed.

These changes suggest that ampicillin can mildly calm acute inflammation, which explains why some patients feel less “feverish” even before the bacteria are fully cleared.

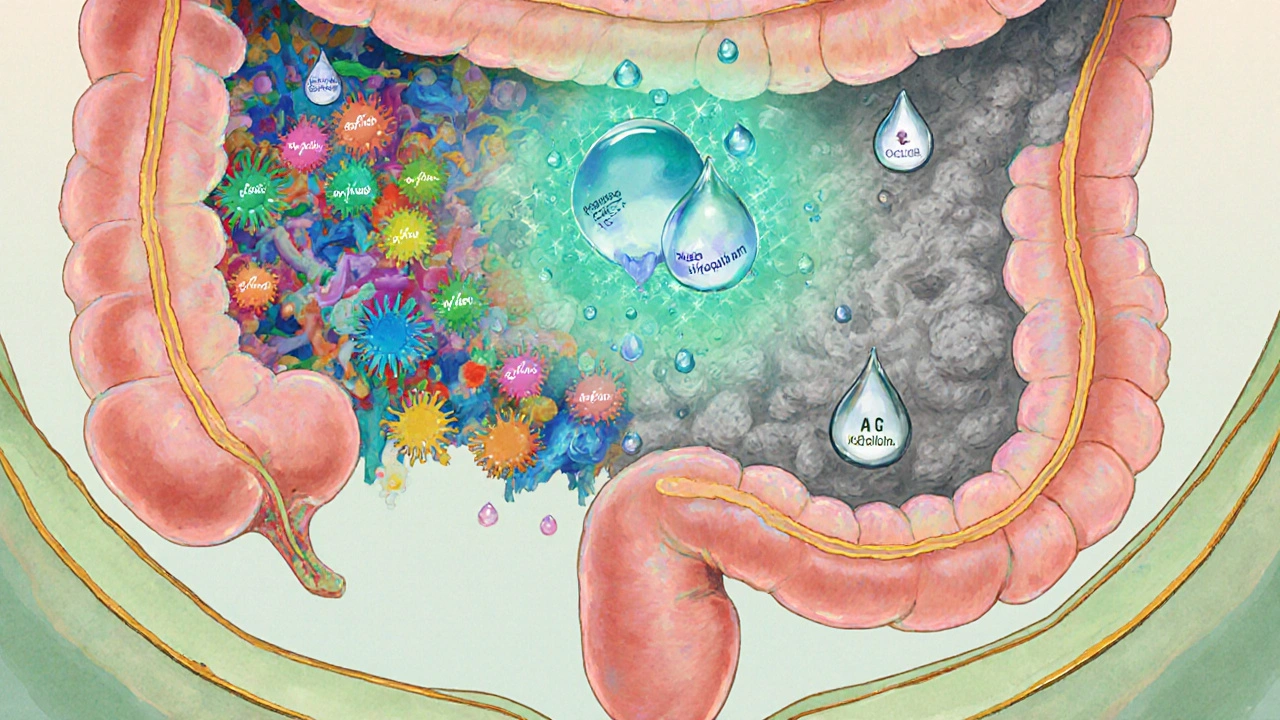

Gut Microbiota: The Hidden Bridge

The gut hosts trillions of microbes that train the immune system. Ampicillin, being orally bioavailable, reaches the colon in low concentrations and can knock down susceptible bacterial families such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus. A 2023 metagenomic study found a 30% reduction in overall diversity after a standard 10‑day course.

Loss of these beneficial microbes translates to lower production of short‑chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, which are known to reinforce the gut barrier and encourage regulatory T‑cell (Treg) development. Consequently, a short‑term dip in SCFAs can tip the immune balance toward a more pro‑inflammatory state, especially in vulnerable individuals.

Most people recover their microbiome within 4‑6 weeks post‑treatment, but repeated courses increase the risk of lasting dysbiosis and pave the way for opportunistic infections such as Clostridioides difficile.

Clinical Implications: When the Trade‑off Matters

Doctors weigh the direct antibacterial power of ampicillin against its indirect immune effects. Here are common scenarios:

- Simple infections (e.g., sinusitis, uncomplicated UTIs): The immune‑modulating side effects are minimal, and the benefit of rapid bacterial clearance outweighs them.

- Patients with autoimmune disorders: A mild anti‑inflammatory push from ampicillin might be helpful, but clinicians monitor cytokine levels closely.

- Elderly or immunocompromised individuals: Reduced neutrophil burst combined with gut dysbiosis can raise infection risk; alternative antibiotics with narrower spectra are often preferred.

Comparison with Other Beta‑Lactams

| Antibiotic | Neutrophil Impact | Cytokine Change (IL‑6) | Gut Microbiota Disruption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin | -10% oxidative burst | -18% after 7 days | ≈30% diversity loss |

| Amoxicillin | -5% oxidative burst | -10% after 7 days | ≈20% diversity loss |

| Cephalexin | No significant change | ±2% (neutral) | ≈15% diversity loss |

| Piperacillin‑tazobactam | -12% oxidative burst | -22% after 5 days | ≈35% diversity loss |

The table shows that ampicillin sits in the middle of the pack: it modestly affects neutrophils and cytokines, but its gut impact is higher than some newer agents like cephalexin.

Practical Tips for Patients on Ampicillin

- Finish the prescription: Stopping early can leave residual bacteria that may trigger a stronger immune reaction later.

- Probiotics: Taking a high‑quality, multi‑strain probiotic (e.g., containing Bifidobacterium lactis and Lactobacillus rhamnosus) during and after treatment helps restore diversity.

- Hydration and fiber: Adequate water and soluble fiber (oats, apples) fuel beneficial gut bacteria.

- Monitor for side‑effects: Persistent diarrhea, severe abdominal pain, or fever after finishing the course could signal C. difficile infection - seek medical care promptly.

Future Directions: Tailoring Antibiotics to the Immune Profile

Scientists are exploring “immune‑friendly” antibiotics that spare gut microbes while retaining potency. One promising avenue is the use of beta‑lactamase inhibitors combined with narrow‑spectrum agents, which may reduce collateral damage.

Personalized medicine could soon match a patient’s microbiome fingerprint with the antibiotic that least disrupts their immune balance. Until then, understanding the trade‑offs of drugs like ampicillin remains the best tool for clinicians and patients alike.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does ampicillin weaken the immune system?

It causes a modest, reversible dip in neutrophil activity and a slight reduction in inflammatory cytokines. For most healthy adults, the effect is not clinically significant.

Can I take probiotics with ampicillin?

Yes. Probiotics containing strains like Lactobacillus rhamnosus or Bifidobacterium lactis can help replenish gut bacteria lost during treatment.

Why does ampicillin sometimes cause diarrhea?

The drug disrupts the normal gut microbiota, allowing opportunistic bacteria to proliferate. This imbalance can lead to watery stools or, in severe cases, C. difficile infection.

Is ampicillin safe for pregnant women?

Ampicillin is classified as pregnancy category B, meaning animal studies show no risk and there are no well‑controlled human studies. Doctors usually consider it safe when the benefits outweigh potential risks.

How long does it take for the gut microbiome to recover after ampicillin?

Most healthy adults see a return to baseline diversity within 4‑6 weeks, though some specific strains may take longer, especially after repeated courses.

Understanding the interaction between ampicillin immune system dynamics helps you make smarter choices about treatment and recovery. Talk to your healthcare provider if you have concerns about side‑effects or want guidance on probiotic use.