Over 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. are filled with generic drugs. They’re cheaper, widely available, and trusted. But if you’ve recently tried to fill a prescription for levothyroxine, epinephrine, or even antibiotics like amoxicillin, you might have been met with a heartbreaking answer: out of stock. This isn’t a fluke. It’s a systemic collapse hiding in plain sight.

How We Got Here

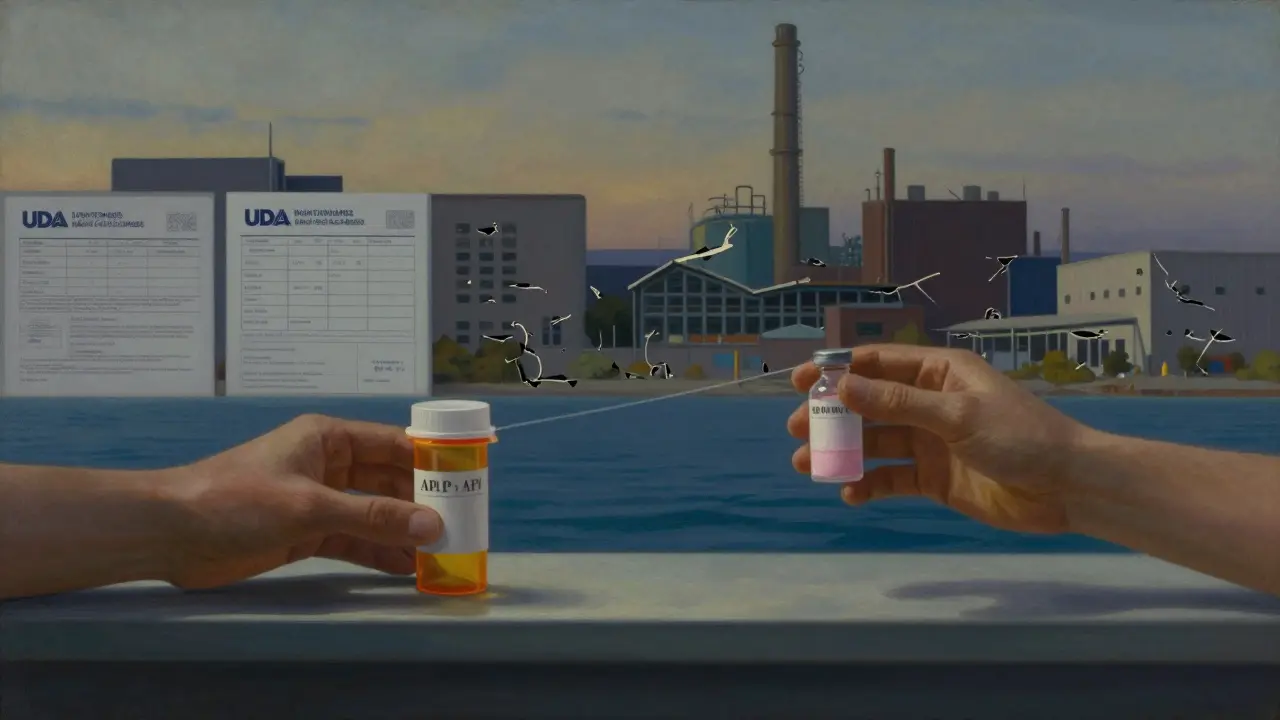

The system that made generics affordable started with the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. It let companies copy branded drugs without repeating expensive clinical trials. The idea was simple: more competition = lower prices. And it worked. Generics now make up 90% of prescriptions but only 20% of total drug spending. Sounds great, right? But here’s the catch: the model only works if manufacturers can make a profit. And today, they can’t. Group purchasing organizations (GPOs) and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) negotiate contracts based on price differences as small as one-tenth of a cent per tablet. That’s not a typo. A single pill might be sold for less than a penny. When a new company enters the market and undercuts by half a cent, everyone else is forced to follow - or lose the contract. The result? A race to the bottom. Margins for generic manufacturers have dropped from 20% in the 2000s to as low as 5% on some drugs. Some companies are literally losing money on every bottle they sell.Where the Medicine Comes From

Most people assume the pills in their bottle were made in the U.S. They weren’t. As of 2023, 72% of the facilities making active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) - the actual medicine inside the pill - are overseas. Over 90% of antibiotics, antivirals, and the top 100 generic drugs rely on foreign-made APIs. China and India dominate this space. About 50% of contract manufacturing for U.S. generics happens in India. China supplies 80% of the raw material for acetaminophen. This isn’t just about cost - it’s about control. These countries have lower labor costs, lighter regulations, and faster approvals. But that also means less oversight. In 2022, the FDA shut down a major Indian manufacturer, Intas Pharmaceuticals, after finding "enormous and systematic quality problems" in their production of cisplatin, a critical cancer drug. That single recall left thousands of patients without treatment. The FDA doesn’t have enough inspectors to keep up. There are over 4,000 foreign drug facilities, but only a few hundred inspectors. Many get inspected once every five years - if they’re lucky.Why Quality Suffers

Making a generic drug isn’t just mixing chemicals. It’s a precise science. The size of particles, the coating on the pill, the rate at which the drug dissolves - all of it has to match the original brand exactly. If one step goes wrong, the drug won’t work the same way. Many generic manufacturers still use outdated batch manufacturing. It’s cheaper, but it’s unreliable. Each batch can vary slightly. Modern continuous manufacturing, which monitors every step in real time, reduces errors dramatically. But it costs $50 million to $100 million to install. No company making 5-cent pills can afford that. Documentation is another problem. U.S.-based manufacturers maintain 95%+ accuracy in their production records. Some foreign facilities? As low as 78%. When the FDA shows up unannounced and finds missing logs, incorrect temperatures, or unclean equipment, they issue a Form 483. Fixing one of those issues takes 12 to 18 months - and costs over $1.7 million. Most companies can’t afford to fix it. So they just stop making the drug.

The Domino Effect

When one manufacturer shuts down or gets shut down, the ripple effect is immediate. Take Akorn Pharmaceuticals. In February 2023, they went bankrupt and stopped producing dozens of generic drugs overnight. Among them: injectable epinephrine, used in emergency rooms for anaphylaxis. No one else could make it fast enough. Hospitals scrambled. Patients risked death. That’s not an exception. It’s the rule. In 2023, the FDA recorded 278 active drug shortages - the highest number since tracking began in 2011. Two-thirds of them were generic drugs. Cancer meds. Heart medications. Antibiotics. Insulin. Even common painkillers like acetaminophen. A 2023 study found that generic drugs made overseas had 54% more serious adverse events - including hospitalizations and deaths - compared to identical drugs made in the U.S. That doesn’t mean all foreign-made generics are dangerous. But it does mean the risk is higher. And when a patient’s thyroid medication suddenly switches brands because the original is gone, they need careful monitoring. One nurse practitioner told Medscape she had to recheck 89 patients’ thyroid levels after a shortage forced a switch.Who Pays the Price

Patients don’t just lose access to their meds - they lose money. When a generic runs out, insurers often force patients onto the branded version. One Medicare beneficiary saw their monthly cost for a heart medication jump from $10 to $450. That’s not a typo. That’s real life. On Reddit’s r/pharmacy, a thread about shortages in early 2023 had over 470 comments from nurses, pharmacists, and doctors. One wrote: “We’ve had to switch antibiotics for 17 different infections in six months. We’re guessing at doses. We’re using older, less effective drugs.” Another said, “I had a patient who skipped her seizure meds for two weeks because we couldn’t get the generic. She had three seizures. She almost died.” The FDA’s drug shortage portal saw complaints rise 327% between 2019 and 2022. People aren’t just annoyed. They’re scared.