When a generic drug hits the market, how do regulators know it works just like the brand-name version? The answer lies in a precise, tightly controlled clinical method called the crossover trial design. This isn’t just a statistical trick-it’s the backbone of nearly every bioequivalence study approved by the FDA and EMA. Unlike studies that compare different groups of people, crossover trials use the same people as their own control. That single shift changes everything: smaller sample sizes, sharper results, and fewer confounding variables. But get it wrong, and the whole study fails.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence

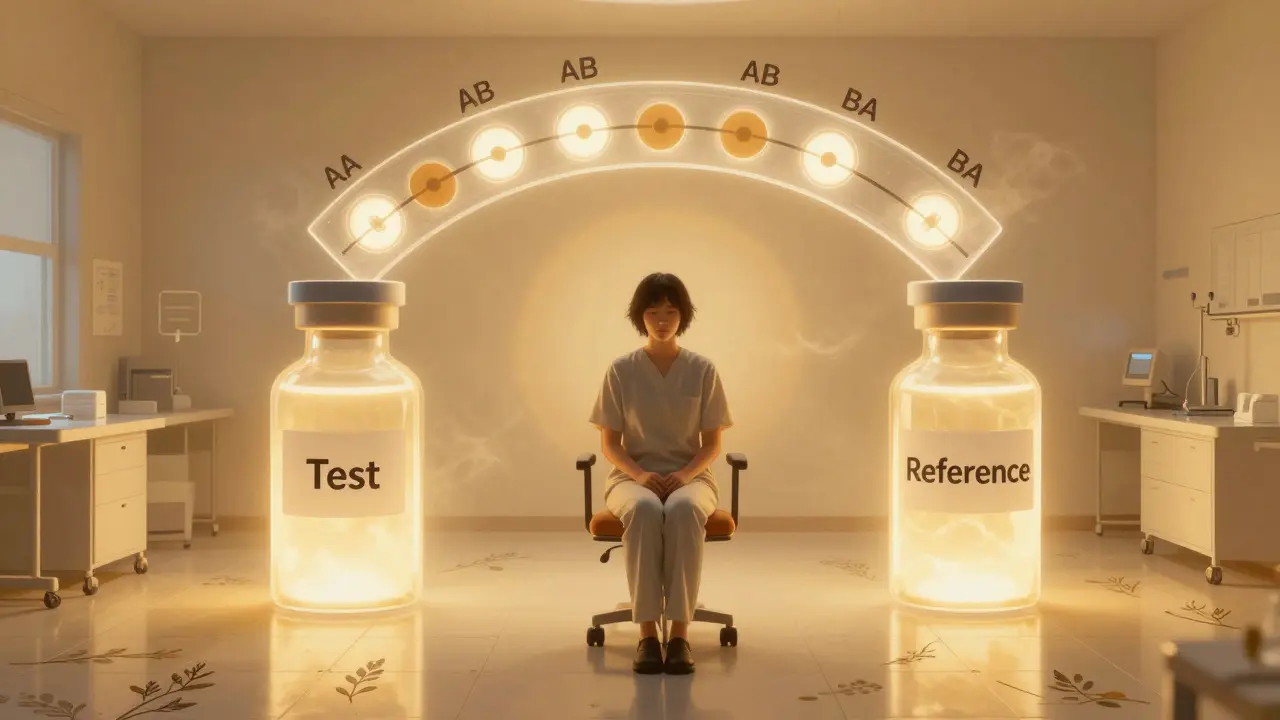

Imagine testing two painkillers. In a parallel design, one group gets Drug A, another gets Drug B. Differences in age, metabolism, or even diet between groups can muddy the results. In a crossover design, each person takes both drugs-first one, then the other-after a clean break. This eliminates between-person variability. The only thing left to measure is the real difference between the drugs themselves. This efficiency is why 89% of bioequivalence studies submitted to the FDA in 2022-2023 used crossover designs. For a standard drug, a 2×2 crossover (two periods, two sequences: AB and BA) can cut the needed participants by up to 80% compared to a parallel study. If the between-subject variation is twice the measurement noise, you only need one-sixth the number of volunteers. That means faster studies, lower costs, and quicker access to affordable generics.The Standard Blueprint: 2×2 Crossover

The most common setup is the two-period, two-sequence design. Participants are randomly assigned to one of two paths:- Sequence AB: Test drug first, then reference drug

- Sequence BA: Reference drug first, then test drug

When the Drug Is Too Variable: Replicate Designs

Not all drugs play nice. Some, like warfarin, clopidogrel, or certain antiretrovirals, show high intra-subject variability-meaning the same person’s blood levels jump around a lot from dose to dose. For these, the standard 80-125% range is too strict. A 2×2 design would need hundreds of participants to have enough power. That’s where replicate crossover designs come in. Instead of one dose of each, participants get multiple doses:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Test drug once, reference drug twice

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Both drugs given twice

Where Crossover Designs Fall Short

Crossover isn’t magic. It fails when the washout isn’t long enough. One statistician reported a $195,000 study failure because residual drug from the first period skewed the second. That’s why validation matters: you can’t just assume the half-life. You need published data or pilot studies to confirm drug clearance. Crossover also doesn’t work for drugs with extremely long half-lives-think 2+ weeks. Waiting five half-lives could mean months between doses. That’s impractical for participants and too expensive for sponsors. For those, parallel designs are the only option. Carryover effects are another silent killer. Even with a proper washout, some drugs linger in tissues or alter metabolism. Regulatory guidelines require testing for sequence-by-treatment interaction. If that effect is significant, the study is invalid. Many rejected applications fail here-not because the drugs aren’t equivalent, but because the design didn’t account for hidden influences.Implementation Pitfalls and Real-World Lessons

A clinical trial manager saved $287,000 and eight weeks by switching from a parallel to a 2×2 crossover for a generic warfarin study. The intra-subject CV was 18%, so 24 participants were enough. In a parallel design, they’d have needed 72. But the same team once botched a replicate design because they used a 7-day washout for a drug with a 10-hour half-life. The math was wrong. They had to restart. The lesson? Don’t guess washout periods. Calculate them. Document them. Validate them. Biostatisticians need specialized training. Common mistakes include:- Using simple t-tests instead of mixed-effects models

- Ignoring period effects in the analysis

- Imputing missing data in a way that breaks the self-controlled structure

What’s Next for Crossover Designs?

The trend is clear: replicate designs are growing. In 2022, they made up 25% of all bioequivalence studies. By 2025, that number could hit 40%. The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance now permits 3-period designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs-drugs where even small differences can be dangerous. The EMA’s 2024 update will likely make full replicate designs the preferred option for all highly variable drugs. Adaptive designs-where sample size is adjusted mid-study based on early data-are also gaining ground. In 2022, 23% of FDA submissions included adaptive elements, up from 8% in 2018. But the core won’t change. Crossover designs remain the gold standard because they answer the question directly: Is this generic the same as the brand, in the same people? As complex generics rise-think inhalers, injectables, topical creams-the need for precise, efficient, and statistically robust methods will only grow. Crossover designs aren’t going away. They’re evolving.How to Know If a Study Used a Valid Crossover Design

If you’re reviewing a bioequivalence report, ask these five questions:- Was the design clearly labeled (2×2, TRR, TRTR)?

- Was the washout period justified with pharmacokinetic data?

- Were sequence, period, and treatment effects tested in the model?

- Was carryover tested (sequence × treatment interaction)?

- For highly variable drugs, was RSABE used-and was the CV above 30%?

What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control. This eliminates variability between different people-like differences in age, weight, or metabolism-making it easier to detect real differences between the test and reference drugs. As a result, crossover designs require far fewer participants than parallel designs to achieve the same statistical power.

Why is a washout period necessary in crossover trials?

A washout period ensures that the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. If traces remain, they can interfere with the second treatment’s absorption or effect-a phenomenon called carryover. Regulators require washout periods of at least five elimination half-lives, backed by data showing drug concentrations fell below the lower limit of quantification.

When is a replicate crossover design used instead of a standard 2×2 design?

Replicate designs (like TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) are used for highly variable drugs-those with an intra-subject coefficient of variation greater than 30%. These designs allow regulators to estimate within-subject variability for both the test and reference products, which enables the use of reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE). This adjusts the equivalence limits based on how variable the reference drug is, making approval feasible without requiring hundreds of participants.

What are the most common reasons crossover bioequivalence studies fail?

The most common failure is inadequate washout periods, leading to carryover effects. Other major issues include improper statistical modeling (like using t-tests instead of mixed-effects models), failing to test for sequence effects, and incorrectly handling missing data. About 15% of major deficiencies in FDA submissions in 2018 were due to flawed crossover implementation.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives-typically over two weeks-because the required washout period would be impractically long. In these cases, parallel designs are required. They’re also not ideal for drugs that cause permanent changes to the body (like some vaccines or irreversible inhibitors), since the effect of the first dose can’t be undone.