When seniors take pain meds, sleep aids, or anxiety drugs, their bodies don’t process them like younger adults. Their liver slows down. Their kidneys filter less. Their brain becomes more sensitive. That means even a normal dose can push them into dangerous over-sedation-or worse, a life-threatening overdose. The signs aren’t always obvious. A quiet, still elderly person might not be peacefully napping. They might be slipping into respiratory failure. This isn’t rare. In the U.S., seniors make up 65% of all respiratory arrests during sedation. But with the right monitoring, most of these events can be prevented.

What Over-Sedation Looks Like in Seniors

- Slowed breathing-fewer than 8 breaths per minute. This is the biggest red flag. It doesn’t always come with gasping or wheezing. Sometimes, it’s just… quiet.

- Unresponsiveness-if you shake their shoulder and they don’t open their eyes or respond to their name, that’s not normal drowsiness. It’s deep sedation.

- Blue or gray lips-this means oxygen is dropping. But don’t wait for this. Many seniors on oxygen won’t turn blue even when their blood oxygen is dangerously low.

- Confusion or agitation-sometimes, over-sedation looks like the opposite of calm. They may become restless, combative, or talk nonsense. This is the brain struggling to process what’s happening.

- Low blood pressure-systolic pressure under 90 mmHg. This often happens after sedatives hit the bloodstream too hard.

These signs don’t always appear together. One nurse in a Mayo Clinic study saw an 82-year-old patient with perfectly normal oxygen levels-until her breathing rate dropped to 6 breaths per minute. She was silent. No snoring. No gasping. Just still. That’s why checking breathing rate isn’t optional. It’s essential.

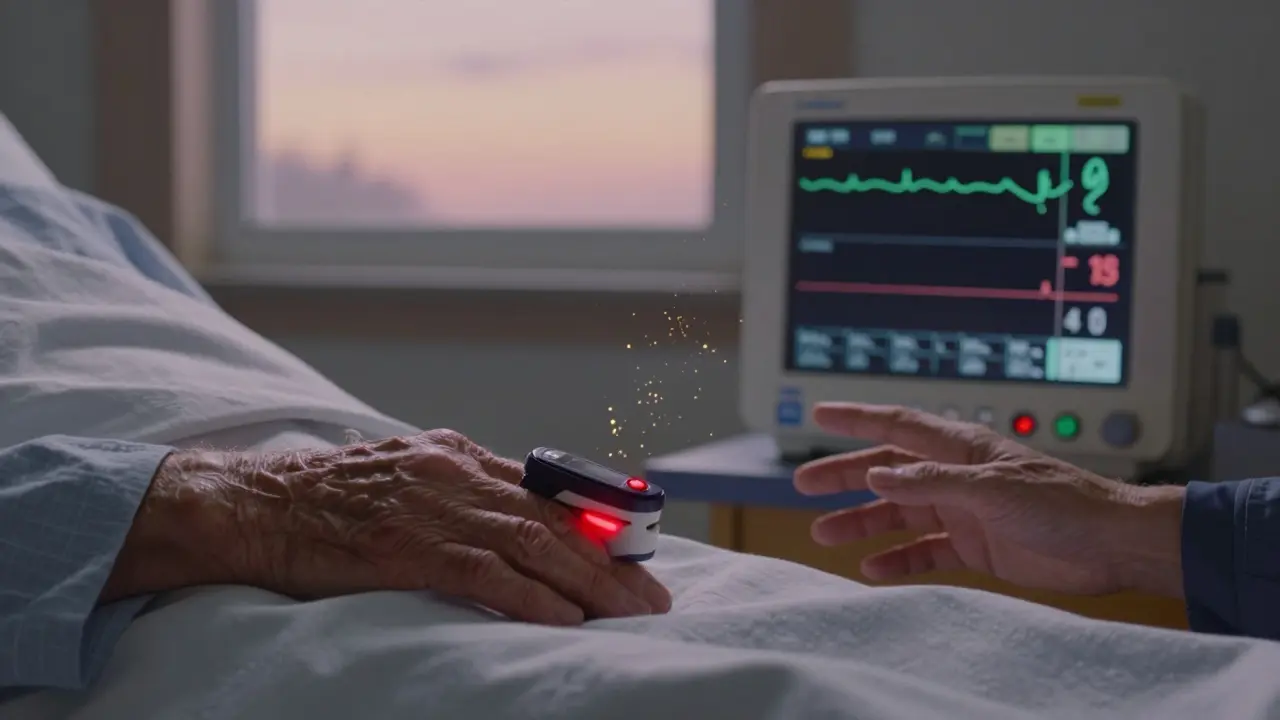

Why Pulse Oximetry Alone Isn’t Enough

Most caregivers and even some nurses rely on pulse oximeters-the little clip on the finger that shows oxygen levels. But in seniors, especially those on supplemental oxygen, this tool can lie.

Here’s why: if a senior is breathing too slowly but getting extra oxygen through a nasal cannula, their SpO2 reading might stay at 94% or higher-even when their body is drowning in carbon dioxide. This is called “silent hypoxia.” It’s the silent killer in geriatric sedation. A 2020 study of 387 seniors found that pulse oximetry alone missed 25% of dangerous breathing pauses. Capnography, which measures carbon dioxide levels in exhaled breath, catches these events 92% of the time.

Capnography shows a waveform-like a graph-of each breath. When it flattens out or becomes irregular, it’s a clear signal that breathing is failing. The problem? Many outpatient clinics and even some hospitals still don’t use it. Only 28% of outpatient endoscopy centers in the U.S. have capnography for seniors, compared to 81% in hospitals. That gap costs lives.

The Gold Standard: Multimodal Monitoring

There’s no single device that tells you everything. You need layers.

Here’s what the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) recommends for seniors over 65:

- Continuous pulse oximetry-set alarms at 90% SpO2. Never ignore a low reading, even if the patient looks fine.

- Continuous capnography-watch for EtCO2 below 35 mmHg or above 45 mmHg. A drop below 30 mmHg means severe hypoventilation.

- Heart rate and blood pressure-check every 5 minutes. Heart rate below 50 or above 100 beats per minute is a warning. Systolic BP below 90 needs immediate action.

- Level of consciousness-use the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS). A score of -2 means moderate sedation. -3 or lower means deep sedation. At -4 or -5, the patient is unarousable. That’s an emergency.

The Integrated Pulmonary Index (IPI) combines all four of these into one number from 1 to 10. A score below 7 means trouble. In a 2021 study of 1,245 seniors, IPI detected respiratory problems 12.7 minutes before oxygen levels dropped. That’s enough time to reverse the overdose before it becomes fatal.

Dosing Matters More Than You Think

Doctors often give seniors the same dose they’d give a 40-year-old. That’s dangerous.

After age 60, the body’s ability to break down sedatives drops by 30-50%. A standard 5 mg dose of midazolam might be fine for a young adult. For an 80-year-old, it can cause a respiratory arrest. The formula for safer dosing is simple: dose = standard dose × (1 - 0.005 × (age - 20)).

For a 75-year-old: 5 mg × (1 - 0.005 × 55) = 5 mg × 0.725 = 3.6 mg. That’s the maximum safe starting dose. Many providers still give the full 5 mg. That’s why 42% of facilities still use adult dosing for seniors, according to the ASA. This isn’t negligence-it’s ignorance. And it’s fixable.

What to Do When You See Warning Signs

If you notice any of the signs above, don’t wait. Act fast.

- Stop all sedatives-immediately. No more pills, no more IV drips.

- Call for help-alert a nurse or emergency response team. Don’t assume someone else is doing it.

- Give oxygen-if they’re not already on it, start it now. But don’t rely on it to fix the problem. It’s a bandage, not a cure.

- Use naloxone if opioids are involved-if the senior took morphine, oxycodone, fentanyl, or any opioid, give naloxone (Narcan). It reverses opioid overdose in minutes. Even if you’re not sure, give it. It’s safe.

- Position them safely-lay them on their side. This keeps the airway open. Don’t let them lie flat on their back.

One case from Massachusetts General Hospital in 2021 ended in death because a 90-year-old patient was left alone during a PEG tube procedure. Staff checked oxygen every 10 minutes. The patient’s breathing slowed to 5 breaths per minute. The oximeter stayed at 95%. They didn’t notice until it was too late. Continuous monitoring could have saved them.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

Even with the right tools, mistakes happen.

- Alarm fatigue-nurses hear so many false alarms that they start ignoring them. Capnography in seniors has a 38% false alarm rate due to irregular breathing. Solution: train staff to interpret waveforms, not just react to beeps.

- Skin damage-continuous electrodes can break fragile skin. Solution: use hydrocolloid dressings under sensors. Studies show this cuts skin injuries by 67%.

- Ignoring COPD-32% of seniors over 65 have chronic lung disease. Their capnography waveforms look different. Solution: get trained in COPD-specific waveform interpretation.

- Thinking “they’re just tired”-this is the most dangerous assumption. A quiet senior isn’t always resting. Sometimes, they’re disappearing.

Technology Is a Tool, Not a Replacement

Devices like the Opioid Risk Monitoring System (ORMS) now automatically pause opioid infusions if breathing drops below 8 breaths per minute. In a 2022 trial, it cut respiratory depression in seniors by 58%. That’s huge.

But no machine replaces a trained human. A 2023 report found that 28% of monitoring failures happened because staff trusted the machine too much. One case in the NCEPOD report showed a nurse ignoring SpO2 readings of 87-91% because “the patient looked fine.” She was wrong. The patient died.

Technology gives you data. Your eyes, ears, and hands tell you what it means.

What Families and Caregivers Can Do

You don’t need a medical degree to help. Here’s how:

- Ask if capnography will be used-if your loved one is getting sedation, ask: “Will you be monitoring breathing with capnography?” If they say no, push for it.

- Know the signs-print out a list of over-sedation symptoms. Keep it by the bed.

- Speak up-if your parent stops responding, say: “Something’s wrong. Check their breathing.” Don’t wait for someone else to notice.

- Ask about dosing-“Is this dose adjusted for their age?” If the answer is “We always give this dose,” that’s a red flag.

One daughter in Oregon saved her 84-year-old father’s life during a colonoscopy by noticing his breathing had slowed. She told the nurse, who checked the capnography monitor. The IPI score was 5.1. They reversed the sedation before he lost consciousness.

Final Thoughts

Over-sedation in seniors isn’t an accident. It’s a system failure. We have the tools. We have the science. We have the guidelines. What’s missing is consistent action.

Every senior deserves to be monitored with the same care we’d give a child. That means continuous breathing checks. It means adjusted doses. It means listening when the body speaks-even when it’s quiet.

The next time you see an elderly person sedated, ask yourself: Are we watching their breathing-or just their fingers?

What are the first signs of over-sedation in seniors?

The earliest signs are slowed breathing (fewer than 8 breaths per minute), unresponsiveness to gentle shaking, and confusion or agitation. These can appear before oxygen levels drop, especially if the senior is on supplemental oxygen. Always check breathing rate first.

Can pulse oximetry miss an overdose in seniors?

Yes. Seniors on oxygen can maintain normal SpO2 readings even while dangerously hypoventilating. This is called silent hypoxia. Capnography, which measures carbon dioxide, catches these events 92% of the time-compared to 67% for pulse oximetry alone.

Should seniors get lower doses of sedatives?

Yes. After age 60, metabolism slows by 30-50%. Use this formula: standard dose × (1 - 0.005 × (age - 20)). For a 75-year-old, that means reducing a 5 mg dose to about 3.6 mg. Many facilities still use adult doses, which increases overdose risk.

Is capnography necessary for all seniors?

The American Society of Anesthesiologists recommends capnography for all seniors over 65 during procedural sedation. It’s especially critical for those with lung disease, obesity, or on opioids. It’s not optional-it’s the minimum standard for safety.

What should I do if I suspect an overdose?

Stop all sedatives immediately. Call for help. Give oxygen if available. If opioids were used, administer naloxone (Narcan). Position the person on their side. Do not wait for symptoms to worsen. Time is critical.

Can technology prevent all overdoses?

No. Even advanced systems like the Opioid Risk Monitoring System reduce events by 58%, but they don’t eliminate risk. Human assessment is still required. Over-reliance on machines caused 28% of monitoring failures in reported cases. Always combine technology with clinical judgment.